Exploration of Issues Related to the LA–ICP–MS U–Pb Dating Technique

-

摘要:

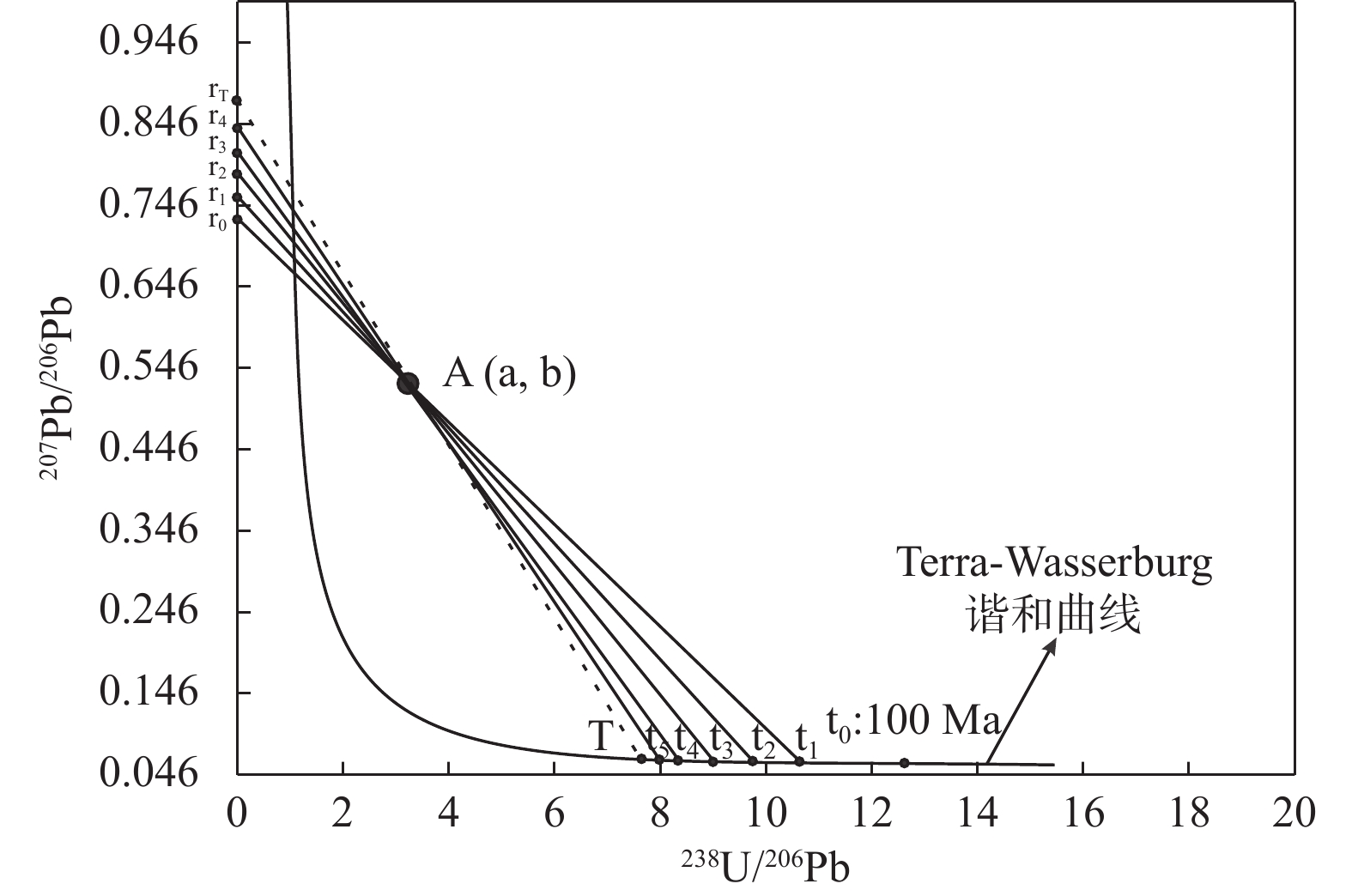

LA–ICP–MS U–Pb定年技术是地质科学中被广泛应用的重要手段。发展至今,该技术已相对成熟,但在实际工作中仍需要注意一些关键问题。笔者就该技术的样品准备、定年结果的取舍、铅丢失问题、普通铅问题和定年结果投图与解释等5个方面进行简要探讨。研究认为,对于复杂矿物进行U–Pb定年研究建议不分选出单矿物,而是采用矿物识别定位手段和LA–ICP–MS仪器相结合的技术手段,直接在岩石光片或探针片上进行原地原位微区定年分析,但要注意样品准备过程中可能存在的铅污染问题。在碎屑矿物定年结果选择方面,对于大于1.5 Ga的定年测点,笔者建议采用207Pb/206Pb年龄代表该颗粒的结晶年龄,而对于小于1.5 Ga的定年测点则应采用206Pb/238U年龄。对沉积岩最大沉积年龄的判断和选择主要依靠统计学方法,必要时需要结合地球化学数据和地质背景信息作为辅助判断依据。对于连续分布在谐和线上的年轻样品要提高警惕,需要采用谐和图、加权平均图、CL图像和元素含量等多种手段识别是否存在铅丢失不一致线。针对普通铅校正问题,笔者重点介绍了一种专用于碎屑矿物U–Pb定年的普通铅校正方法,并给出了计算过程。关于对矿物U–Pb定年结果加权平均值数据质量的评价,笔者着重讨论MSWD越接近于1表示数据质量越高的理论基础。总之,应用LA–ICP–MS 技术对矿物进行U–Pb定年研究需要综合考虑多个因素,才能得出准确、可靠和地质意义明确的定年结果。

-

关键词:

- LA–ICP–MS U–Pb定年 /

- 最大沉积年龄 /

- 铅丢失 /

- 普通铅 /

- MSWD

Abstract:The LA–ICP–MS U–Pb dating technique is a crucial tool that has been widely employed in geological sciences. Despite its relative maturity, several critical issues still require attention in practical applications. This article provides a brief discussion of five critical aspects of this technique, including sample preparation, selection of dating results, lead loss, common lead, and presentation and interpretation of dating results. Firstly, for the U–Pb dating of complex minerals, it is recommended to employ mineral identification and location techniques in combination with LA–ICP–MS instruments for in–situ analysis directly on rock thin sections or polished sections, without mineral separation. However, attention must be paid to Pb contamination in sample preparation. Secondly, for the selection of dating results for detrital minerals, the 206Pb/207Pb age is utilized to represent the crystallization age of grains older than 1.5 Ga, while the 206Pb/238U age is employed for grains younger than 1.5 Ga. The determination and selection of the maximum depositional age of sedimentary rocks mainly rely on statistical methods and sometimes require the combination of geochemical data and geological background information as supplementary criteria. Thirdly, for young samples with continuous age distribution on the concordia line, various methods such as the concordia diagram, weighted mean diagram, CL images, and element contents should be used to identify whether there is an inconsistent lead loss line or not. Furthermore, this article focuses on a rarely used common lead correction method for detrital mineral U–Pb dating. Finally, this article emphasizes the theoretical basis that, when evaluating the quality of the weighted mean value, the closer the MSWD is to 1, the higher the data quality is. In summary, to conduct U–Pb dating studies on minerals using LA–ICP–MS technology, it is essential to consider multiple factors comprehensively to obtain accurate, reliable, and geologically meaningful dating results.

-

Key words:

- LA–ICP–MS U–Pb dating /

- maximum depositional age /

- lead loss /

- common lead /

- MSWD

-

-

图 1 锆石U–Pb定年测试数据统计图(37358个)(Voice et al.,2011;Spencer et al., 2016)

Figure 1.

-

[1] Antonio S, Larry M H, Thomas C, et al. In situ petrographic thin section U–Pb dating of zircon, monazite, and titanite using laser ablation–MC–ICP-MS[J]. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 2006, 253, 87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2006.03.003

[2] Becquerel H. Sur les radiations émises par phosphorescence[J]. Comptes Rendus, 1896, 122, 420-421.

[3] Bowes D R. The geology and geochemistry of lead ore deposits[J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 1977, 13(4), 315-384.

[4] Cawood P A, Nemchin A A, Strachan R A. Provenance record of Laurentian passive-margin strata in the northern Caledonides: Implications for paleodrainage and paleogeography[J]. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 2007, 119, 993-1003. doi: 10.1130/B26152.1

[5] Cawood P A, Hawkesworth C J, Dhuime B. Detrital zircon record and tectonic setting [J]. Geology, 2012, 40(10), 875−878.

[6] Condon D J, Bowring S A. A user’s guide to Neoproterozoic geochronology[A]. In Arnaud E, Halverson G P, Shields-Zhou G (Eds.). The Geological Record of Neoproterozoic Glaciations [R]. Geological Society of London, 2011: 135-146.

[7] Chiarenzelli J, Kratzmann D, Selleck B, et al. Age and provenance of Grenville supergroup rocks, Trans-Adirondack Basin, constrained by detrital zircons[J]. Geology, 2014, 43, 183-186.

[8] David J, Chew D, Petrus J. Apatite U-Pb dating with LA-ICP MS[J]. Chemical Geology, 2011, 280(1-2), 1-20. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2010.07.008

[9] Dickinson W R, Gehrels G E. Use of U–Pb ages of detrital zircons to infer maximum depositional ages of strata: A test against a Colorado Plateau Mesozoic database[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2009, 288(1-2), 115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpgl.2009.09.013

[10] Fleet M E. The geochemistry of lead[A]. In Holland H D, Turekian K K (Eds. ). Treatise on geochemistry[M]. Oxford: Elsevier, 2003, 9: 1–51.

[11] Fripiat J J. Lead isotopes in minerals[A]. In Henderson P (Ed. ). Rare earth element geochemistry[M]. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1984: 571–584.

[12] Hiess J, Condon D J, McLean N, et al. 238U/235U systematics in terrestrial uranium-bearing minerals[J]. Science, 2012, 335, 1610–1614. doi: 10.1126/science.1215507

[13] Herriott T M, Crowley J L, Schmitz M D, et al. Exploring the law of detrital zircon: LA-ICP-MS and CA-TIMS geochronology of Jurassic forearc strata, Cook Inlet, Alaska, USA[J]. Geology, 2019, 47(11), 1044-1048. doi: 10.1130/G46312.1

[14] Horstwood M S A, Košler J, Gehrels G, et al. Community-Derived Standards for LA-ICP-MS U-(Th-)Pb Geochronology – Uncertainty Propagation, Age Interpretation and Data Reporting[J]. Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research, 2016, 40(3), 311−332.

[15] Hisatoshi I, Shimpei U, Futoshi N, et al. Zircon U–Pb dating using LA-ICP-MS: Quaternary tephras in Yakushima Island, Japan[J]. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 2017, 338, 92-100. doi: 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2017.02.003

[16] Jaffey A H, Flynn K F, Glendenin L E, et al. Precision measurement of half-lives and specific activities of 235U and 238U[J]. Physical Review C, 1971, 4(5), 1889-1906. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevC.4.1889

[17] Li Y G, Song S G, Yang X Y, et al. Age and composition of Neoproterozoic diabase dykes in North Altyn Tagh, northwest China: implications for Rodinia break-up[J]. International Geology Review, 2023a, 65(7): 1000-1016. doi: 10.1080/00206814.2020.1857851

[18] Li Y, Yuan F, Simon M J, Li X, et al. (2023). Combined garnet, scheelite and apatite U–Pb dating of mineralizing events in the Qiaomaishan Cu–W skarn deposit, eastern China[J]. Geoscience Frontiers, 2023b, 14(1): 17-32.

[19] Lin M, Zhang G, Li N, et al. (2021). An Improved In Situ Zircon U‐Pb Dating Method at High Spatial Resolution (≤ 10 μm spot) by LA‐MC‐ICP‐MS and its Application[J]. Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research, 2021, 45(2): 265-285. doi: 10.1111/ggr.12374

[20] Lin J, Liu Y, Yang Y, et al. Calibration and correction of LA-ICP-MS and LA-MC-ICP-MS analyses for element contents and isotopic ratios[J]. Solid Earth Sciences, 2016. 1(1), 5-27. doi: 10.1016/j.sesci.2016.04.002

[21] Liu E, Zhao J X, Wang H, et al. LA-ICPMS in-situ U-Pb Geochronology of Low-Uranium Carbonate Minerals and Its Application to Reservoir Diagenetic Evolution Studies[J]. Journal of Earth Science, 2021, 32, 872–879. doi: 10.1007/s12583-020-1084-5

[22] Liu Y S, Hu Z C, Li M, et al. Applications of LA-ICP-MS in the elemental analyses of geological samples. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2013, 58, 3863-3878.

[23] Merriman R J. Lead[A]. In Linnen R L, Samson I M (Eds. ). Rare element geochemistry and mineral deposits[R]. Geological Association of Canada Short Course Notes, 2007, 17: 201-230.

[24] Patterson C. Age of meteorites and the Earth[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1956a, 10, 230-237. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(56)90036-9

[25] Patterson C. Isotopic ages of the Earth and Moon[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1956b, 42(4), 194-199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.42.4.194

[26] Rutherford E. A Radioactive Substance emitted from Thorium Compounds[J]. Philosophical Magazine, 1900, 49(293), 1-14.

[27] Richard A C, Derek H C W. U–Pb dating of perovskite by LA-ICP-MS: An example from the Oka carbonatite, Quebec, Canada[J]. Chemical Geology, 2006, 235, 21–3. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2006.06.002

[28] Schaltegger U, Schmitt A K, Horstwood M S A. U-Th-Pb zircon geochronology by ID-TIMS, SIMS and laser ablation ICP-MS: Recipes, interpretations and opportunities[J]. Chemical Geology, 2015, 402, 89-110. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2015.02.028

[29] Spencer C J, Kirkland C L, Taylor R J M. Strategies towards statistically robust interpretations of in situ U–Pb zircon geochronology[J]. Geoscience Frontiers, 2016, 7(4): 581-589. doi: 10.1016/j.gsf.2015.11.006

[30] Spencer C J, Prave A R, Cawood P A, et al. Detrital zircon geochronology of the Grenville/Llano foreland and basal Sauk Sequence in west Texas, USA[J]. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 2014, 126(7-8), 1117-1128. doi: 10.1130/B30884.1

[31] Stacey J S, Kramers J D. Approximation of terrestrial lead isotope evolution by a two-stage model[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 1975, 26(2), 207-221. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(75)90088-6

[32] Tang Y, Cui K, Zheng Z, et al. LA-ICP-MS UPb geochronology of wolframite by combining NIST series and common lead-bearing MTM as the primary reference material: Implications for metallogenesis of South China[J]. Gondwana Research, 2020, 83, 217-231. doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2020.02.006

[33] Vermeesch P. Maximum depositional age estimation revisited[J]. Geoscience Frontiers, 2021, 12(2), 843-850. doi: 10.1016/j.gsf.2020.08.008

[34] Vermeesch P. Multi-sample comparison of detrital age distributions[J]. Chemical Geology, 2013, 341, 140-146. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.01.010

[35] Voice P J, Kowalewski M, Eriksson K A. Quantifying the timing and rate of crustal evolution: global compilation of radiometrically dated detrital zircon grains[J]. The Journal of Geology, 2011, 119: 109-126. doi: 10.1086/658295

[36] Wendt I, Carl C. The statistical distribution of the mean squared weighted deviation. Chemical Geology: Isotope Geoscience section, 1991, 86(4), 275-285.

-

下载:

下载: