Silicic productivity record in the Westen Pacific Warm Pool in the last 700 ka and its climatic effect

-

摘要:

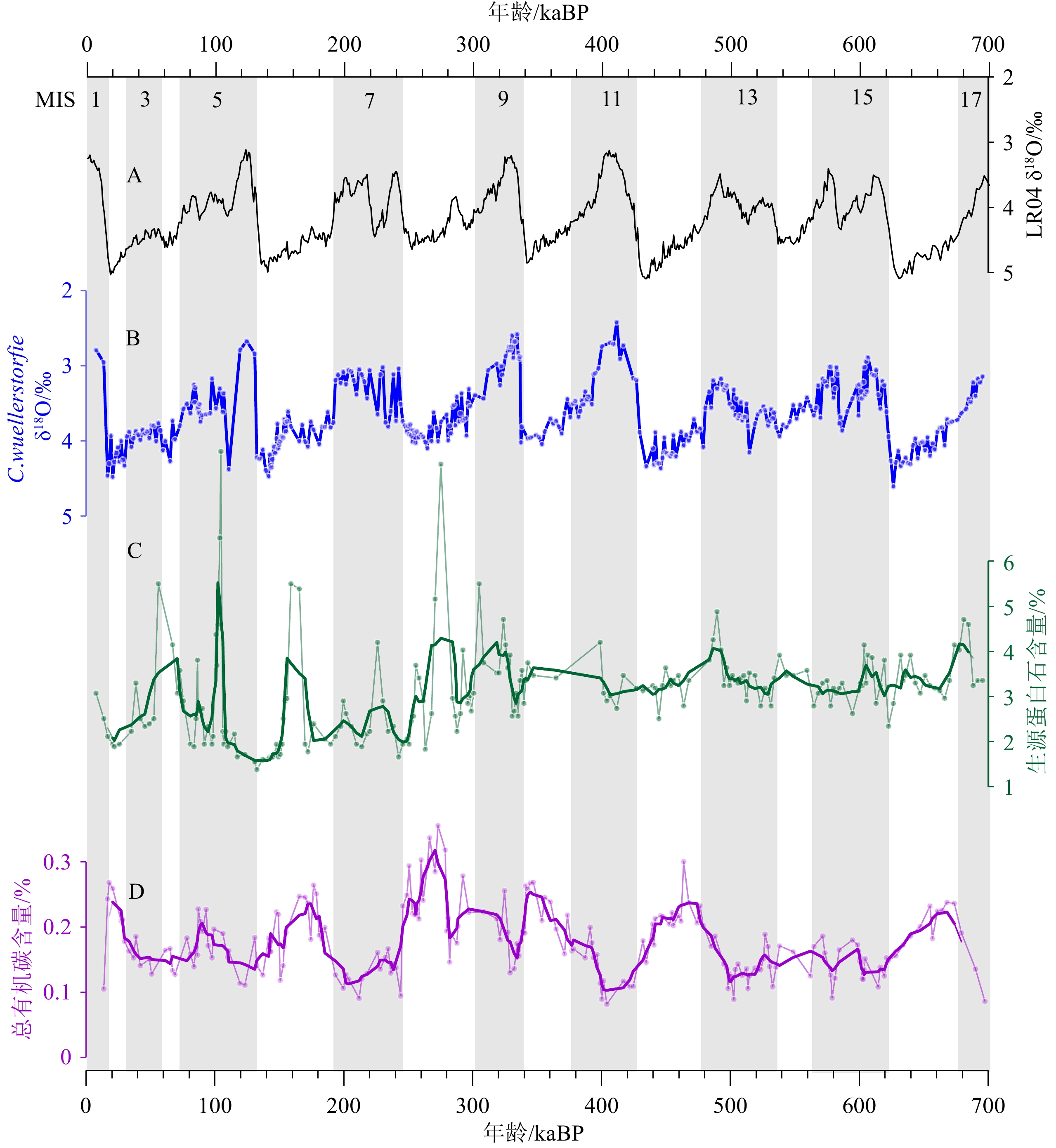

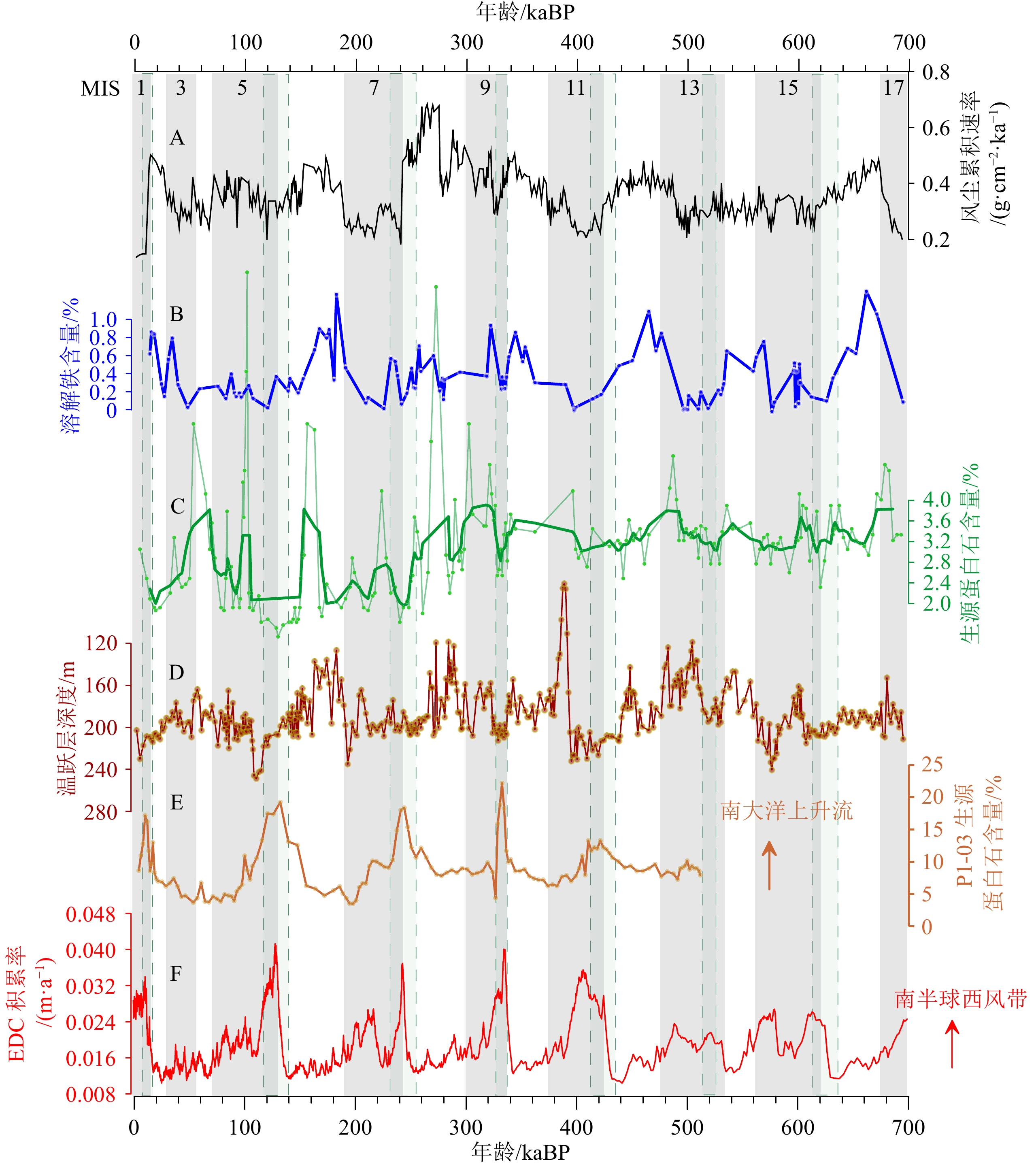

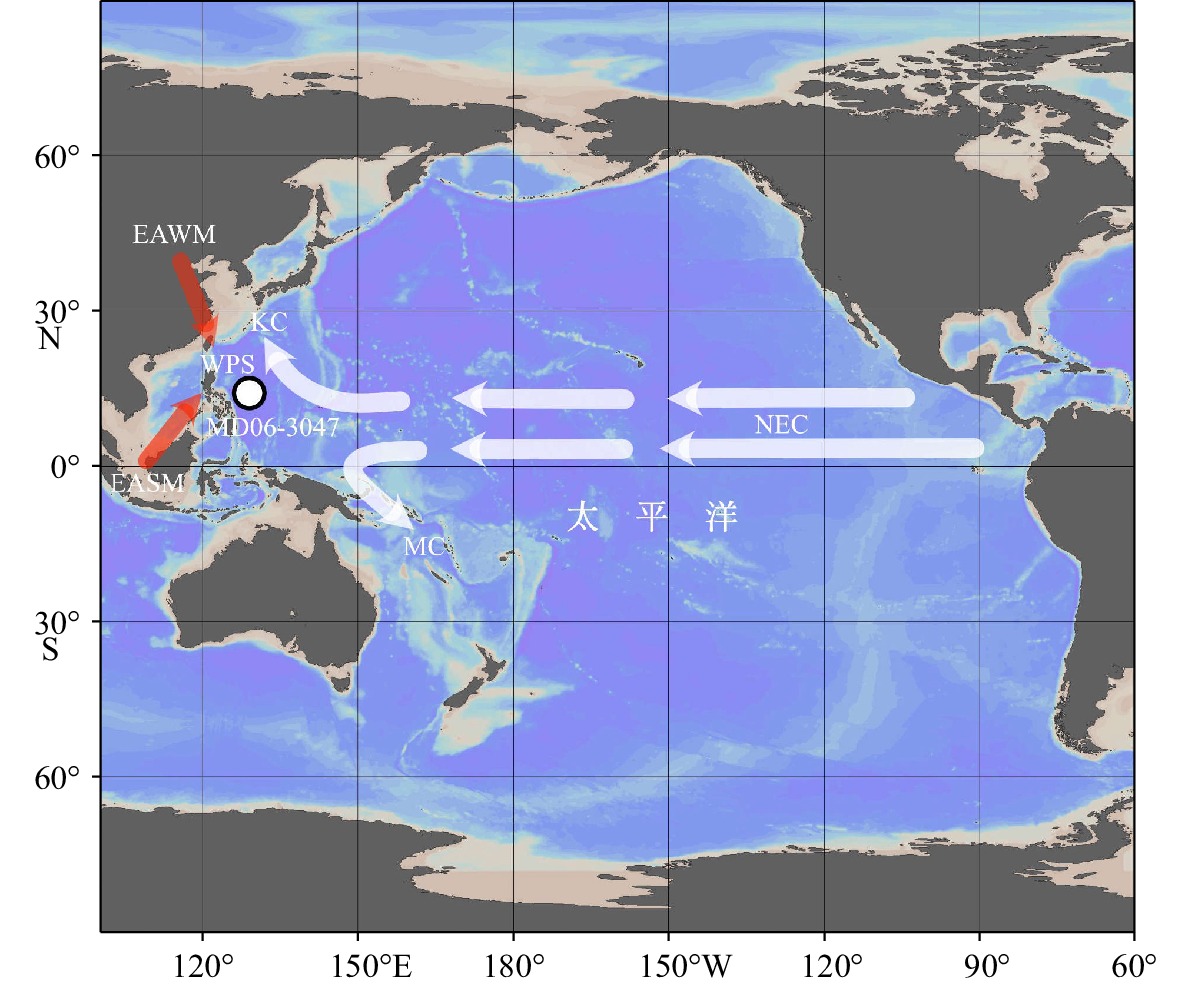

西太平洋暖池(WPWP)的硅质生产力水平在调节第四纪全球大气CO2分压的变化上发挥着重要作用,但其控制因素尚存争议。本研究对位于WPWP核心区的MD06-3047岩芯进行了生源蛋白石分析,探讨了700 ka以来WPWP的硅质生产力的控制因素及气候效应。研究发现,700 ka以来WPWP硅质生产力变化呈现显著的冰期-间冰期旋回,基本在冰期较高,间冰期较低。其主要控制因素可能是东吕宋陆架沉积物风化输入、亚洲风尘输入和温跃层深度(DOT)变化。南大洋中层水的“硅溢漏”可能无法对此海区产生显著影响。冰期时的低海平面,导致热带火山弧附近裸露的陆架沉积物的物理剥蚀和硅酸盐风化,淡水输入为WPWP提供了更多的硅酸;冰期时增强的风尘供应为WPWP提供了更多的Fe;冰期时较浅的DOT使表层海水的营养物质垂向空间变小,滞留时间增多。这些因素使冰期的WPWP生产力增高,有可能降低了大气CO2分压。

Abstract:The Quaternary silicic productivity levels in the Western Pacific Warm Pool (WPWP) are believed to play a crucial role in regulating changes in global atmospheric CO2 partial pressure. However, there is a debate regarding the factors that control the productivity levels. We examined the biogenic opal of core MD06-3047, which is located in the central region of the WPWP, to investigate the controlling factors and climatic effects on silicic productivity over the past 700 kyr. Our findings indicate that the variation in silicic productivity in the WPWP exhibits significant glacial-interglacial cycles: higher levels during glacial periods while lower levels during interglacial periods. The primary controlling factors might be sediment erosion and weathering on the East Luzon continental shelf, the aeolian dust input, as well as the depth of the thermocline (DOT). The silicic acid leakage from the Southern Ocean may not have a significant impact. During glacial periods, physical erosion and silicate weathering of exposed continental shelf sediments near tropical volcanic arcs were intensified, and so did the dust input, which resulted in increased input of silicate and iron to the WPWP. The shallower DOT during glacial periods led to a smaller nutrient vertical space and increased retention time, thereby increasing the glacial productivity of the WPWP, and potentially reducing the partial pressure of atmospheric CO2.

-

Key words:

- Western Pacific Warm Pool /

- biogenic opal /

- sea level /

- depth of the thermocline /

- atmospheric CO2

-

-

[1] Lüthi D, Le Floch M, Bereiter B, et al. High-resolution carbon dioxide concentration record 650, 000-800, 000 years before present[J]. Nature, 2008, 453(7193): 379-382. doi: 10.1038/nature06949

[2] Xiong Z F, Li T G, Crosta X, et al. Potential role of giant marine diatoms in sequestration of atmospheric CO2 during the last glacial maximum: δ13C evidence from laminated Ethmodiscus rex mats in tropical west pacific[J]. Global and Planetary Change, 2013, 108: 1-14. doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2013.06.003

[3] Tang Z, Li T G, Chang F M, et al. Paleoproductivity evolution in the west Philippine sea during the last 700 ka[J]. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 2013, 31(2): 435-444. doi: 10.1007/s00343-013-2117-z

[4] Xiong Z F, Li T G, Algeo T, et al. Paleoproductivity and paleoredox conditions during late Pleistocene accumulation of laminated diatom mats in the Tropical West Pacific[J]. Chemical Geology, 2012, 334: 77-91. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.09.044

[5] Xu Z K, Wan S M, Colin C, et al. Enhanced terrigenous organic matter input and productivity on the western margin of the western pacific warm pool during the quaternary sea-level lowstands: Forcing mechanisms and implications for the global carbon cycle[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2020, 232: 106211. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106211

[6] Sarmiento J L, Gruber N, Brzezinski M A, et al. High-latitude controls of thermocline nutrients and low latitude biological productivity[J]. Nature, 2004, 427(6969): 56-60. doi: 10.1038/nature02127

[7] Bostock H C, Opdyke B N, Williams M J M. Characterising the intermediate depth waters of the Pacific Ocean using δ13C and other geochemical tracers[J]. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 2010, 57(7): 847-859. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2010.04.005

[8] Ragueneau O, Tréguer P, Leynaert A, et al. A review of the Si cycle in the modern ocean: Recent progress and missing gaps in the application of biogenic opal as a paleoproductivity proxy[J]. Global and Planetary Change, 2000, 26(4): 317-365. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8181(00)00052-7

[9] Pondaven P, Ragueneau O, Tréguer P, et al. Resolving the ‘opal paradox’ in the Southern Ocean[J]. Nature, 2000, 405(6783): 168-172. doi: 10.1038/35012046

[10] Nelson D M, Anderson R F, Barber R T, et al. Vertical budgets for organic carbon and biogenic silica in the pacific sector of the Southern Ocean, 1996–1998[J]. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 2002, 49(9-10): 1645-1674. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00005-X

[11] Boyd P W, Watson A J, Law C S, et al. A mesoscale phytoplankton bloom in the polar Southern Ocean stimulated by iron fertilization[J]. Nature, 2000, 407(6805): 695-702. doi: 10.1038/35037500

[12] Qiu B, Lukas R. Seasonal and interannual variability of the north equatorial current, the Mindanao current, and the Kuroshio along the pacific western boundary[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 1996, 101(C5): 12315-12330. doi: 10.1029/95JC03204

[13] Qu T D, Lukas R. The bifurcation of the north equatorial current in the pacific[J]. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 2003, 33(1): 5-18. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(2003)033<0005:TBOTNE>2.0.CO;2

[14] Kim J H, Rimbu N, Lorenz S J, et al. North pacific and north Atlantic sea-surface temperature variability during the Holocene[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2004, 23(20-22): 2141-2154. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.08.010

[15] Dugdale R C, Wischmeyer A G, Wilkerson F P, et al. Meridional asymmetry of source nutrients to the equatorial pacific upwelling ecosystem and its potential impact on ocean–atmosphere CO2 flux; a data and modeling approach[J]. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 2002, 49(13-14): 2513-2531. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00046-2

[16] Locarnini R A, Mishonov A V, Antonov J I, et al. World ocean atlas 2005, vol. 1, temperature[M]//Levitus S. NOAA Atlas NESDIS, vol. 61. Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 2006.

[17] Sigman D M, Hain M P. The biological productivity of the ocean[J]. Nature Education Knowledge, 2012, 3(10): 21.

[18] Xiong Z F, Li T G, Algeo T, et al. The silicon isotope composition of Ethmodiscus rex laminated diatom mats from the tropical west pacific: Implications for silicate cycling during the last glacial maximum[J]. Paleoceanography, 2015, 30(7): 803-823. doi: 10.1002/2015PA002793

[19] Liu Z F, Zhao Y L, Colin C, et al. Chemical weathering in Luzon, Philippines from clay mineralogy and major-element geochemistry of river sediments[J]. Applied Geochemistry, 2009, 24(11): 2195-2205. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2009.09.025

[20] Mortlock R A, Froelich P N. A simple method for the rapid determination of biogenic opal in pelagic marine sediments[J]. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers, 1989, 36(9): 1415-1426. doi: 10.1016/0198-0149(89)90092-7

[21] Lisiecki L E, Raymo M E. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records[J]. Paleoceanography, 2005, 20(1): PA1003.

[22] Thompson P R, Bé A W H, Duplessy J C, et al. Disappearance of pink-pigmented Globigerinoides ruber at 120, 000 yr BP in the Indian and pacific oceans[J]. Nature, 1979, 280(5723): 554-558. doi: 10.1038/280554a0

[23] Xu Z K, Li T G, Clift P D, et al. Quantitative estimates of Asian dust input to the western Philippine Sea in the Mid‐Late Quaternary and its potential significance for paleoenvironment[J]. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 2015, 16(9): 3182-3196. doi: 10.1002/2015GC005929

[24] Wan S M, Clift P D, Zhao D B, et al. Enhanced silicate weathering of tropical shelf sediments exposed during glacial lowstands: A sink for atmospheric CO2[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2017, 200: 123-144. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2016.12.010

[25] Xu Z K, Li T G, Clift P D, et al. Bathyal records of enhanced silicate erosion and weathering on the exposed Luzon shelf during glacial lowstands and their significance for atmospheric CO2 sink[J]. Chemical Geology, 2018, 476: 302-315. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2017.11.027

[26] Beaufort L, De Garidel-Thoron T, Mix A C, et al. ENSO-like forcing on oceanic primary production during the Late Pleistocene[J]. Science, 2001, 293(5539): 2440-2444. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5539.2440

[27] Sun H J, Li T G, Liu C L, et al. Variations in the western pacific warm pool across the Mid-Pleistocene: Evidence from oxygen isotopes and coccoliths in the West Philippine sea[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2017, 483: 157-171. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.07.008

[28] Brzezinski M A, Pride C J, Franck V M, et al. A switch from Si(OH)4 to NO3− depletion in the glacial Southern Ocean[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2002, 29(12): 5-1-5-4.

[29] Tang Z, Shi X F, Zhang X, et al. Deglacial biogenic opal peaks revealing enhanced Southern Ocean upwelling during the last 513 ka[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 425: 445-452. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2016.09.020

[30] Bazin L, Landais A, Lemieux-Dudon B, et al. An optimized multi-proxy, multi-site Antarctic ice and gas orbital chronology (AICC2012): 120–800 ka[J]. Climate of the Past, 2013, 9(4): 1715-1731. doi: 10.5194/cp-9-1715-2013

[31] Spratt R M, Lisiecki L E. A Late Pleistocene sea level stack[J]. Climate of the Past Discussions, 2015, 11: 3699-3728.

[32] Xiong Z F, Li T G, Chang F M, et al. Rapid precipitation changes in the tropical West Pacific linked to North Atlantic climate forcing during the last deglaciation[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2018, 197: 288-306. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.07.040

[33] Chen L Y, Luo M, Dale A W, et al. Reconstructing organic matter sources and rain rates in the southern West Pacific Warm Pool during the transition from the deglaciation period to early Holocene[J]. Chemical Geology, 2019, 529: 119291. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.119291

-

下载:

下载: